Oliver Rackham (Corpus Christi, Cambridge)* – Nicolas Vernicos (Aegean University)

Cite as: Rackham, O., Vernicos, N. (2019). Chalki in the Dodecanese. Archive, 15, pp. 6–31. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.4475437, ARK:/13960/t9n40b015

The paper that follows is a modified version of the original paper of Oliver Rackham and Nicolas Vernicos (1991), «On the ecological history and future prospects of the island of Khalki,» in A.T. Grove, Jennifer Moody and Oliver Rackham, Crete and the South Aegean Islands (effects of changing climate on the environment ). Geography Department, Downing Place, University of Cambridge, E.C. Contract EV4C-0073-UK, February 1991, pp. 347-361.[2] Various additions are included in the paper’s notes, the images and in the annex. (Nicolas Vernicos 2009)

Περίληψη

Η Χάλκη είναι νησί με ελάχιστη βλάστηση και ερημοποιημένο, όπως πολλά νησιά του Αιγαίου, αλλά μέχρι πρόσφατα είχε σχετικά μεγάλο πληθυσμό. Εξετάζουμε την ιστορική οικολογία της κυρίως από τα στοιχεία που περιέχονται στο παρόν τοπίο και τη βλάστηση. Καταλήγουμε στο συμπέρασμα ότι το νησί είναι απίθανο να έχει υποβαθμιστεί πολύ από την ανθρώπινη κακοδιαχείριση. Οι κάτοικοί του, προσεκτικά και με πολύ δουλειά, έχουν κάνει την καλύτερη δυνατή χρήση ενός δύσκολου φυσικού περιβάλλοντος για τουλάχιστον 3.500 χρόνια. Ο πρόσφατος πληθυσμός του δεν έχει καμία σχέση με την περιβαλλοντική αλλαγή. Η «επαναφορά» ενός τέτοιου νησιού σε κατάσταση υψηλής βλάστησης μπορεί να είναι εσφαλμένος στόχος και πρέπει να γίνει προσπάθεια μόνο με μεγάλη προσοχή. Η Χάλκη δίνει στους επισκέπτες της την εντύπωση ενός «νησιού ερήμου». Φεύγοντας από την πλούσια βλάστηση της Ρόδου, το καΐκι πλέει από την Κάμειρο Σκάλα περνώντας από το άνυδρο αλλά σχετικά καταπράσινο νησί της Αλιμνιάς και μπαίνει στον κόλπο του Ιμπορίου, την πρωτεύουσα της Χάλκης, ανάμεσα σε βουνά από γκρίζο και πορτοκαλί ασβεστόλιθο –ένα αυστηρό και ερημικό τοπίο σχεδόν χωρίς ορατή φυτική ζωή. Η πρώτη εντύπωση μετριάζεται από την εύφορη κοιλάδα πίσω από το λιμάνι, με τους υπέροχους τερέβινθους και άλλα όμορφα δέντρα. Ωστόσο, η Χάλκη είναι ένα ακραίο παράδειγμα που αναφέρεται από εκείνους που πιστεύουν ότι τα ελληνικά τοπία έχουν «ερημοποιηθεί» από αιώνες κακοποίησης από ανθρώπους και ζώα. Η πρόταση που έγινε κατά τη δεκαετία του 1980 για την «αποκατάσταση» ή την «αναβίωση» του νησιού, υποδηλώνει ότι κάποτε υπήρχε μια πιο πλούσια βλάστηση και θα μπορούσε να ανακτηθεί με μελλοντική παρέμβαση.

Summary

Chalki is one of the least vegetated and most desert like of the Aegean islands, but until recently had a relatively large population. We examine its historical ecology chiefly from the evidence contained in the present landscape and vegetation. We conclude that the island is unlikely to have been much degraded by human mismanagement. Its inhabitants have carefully and with great labour, made the best use of a difficult natural environment over at least 3500 years[3]. Its recent depopulation has nothing to do with environmental change. To «restore» such an island to a more vegetated state may be a misdirected objective, and should be attempted only with great caution.

Chalki gives its visitors the impression of a “desert island”. Leaving the lush vegetation of Rhodes the caique sails from Kamiros Skala past the arid but relatively green island of Alimnia, and enters the bay of Imborio[4] the capital of Chalki, between frowning mountains of gray and orange limestone – a stern and desolated landscape almost devoid of visible plant life. The first impression is moderated by the fertile valley behind the port, with its great terebinths and other beautiful trees; but nevertheless Chalki is an extreme example quoted by those who believe that Greek landscapes have been «desertified» by centuries of abuse by men and goats. The suggestion that has been made during the 1980’s, for the «restoration» or «reboisement» of the island imply that a more luxuriant vegetation once existed and could be recovered by future intervention.[5]

The Dodecanesian Island of Chalki

Chalki is very mountainous: it is only 4 km wide and has several peaks of 500-600 m. The north coast is a wall of cliffs and there are many lesser cliffs and gorges elsewhere. Cultivable basins and valleys are scattered all over the island.

The bedrock is entirely hard limestone – mostly massive and lacking wide fissures though in places rugged and porous. There are few dolines and caves. The basins and valleys contain up to 6 m depth off Older Fill – a red-brown deposit full of boulders and rock fragments laid down by Pleistocene erosion. A section of Older Fill cut by the sea just above the Pontamos beach reveals several phases of deposition of different sizes of material: intercalated in it is a stratum of aeolianite, a soft sandstone formed by the cementing of dunes (used as a minor building stone at Imborio).

The climate is hot dry, and very evaporative. Strong northerly winds sweep all exposed slopes. Rainfall is much less than on Rhodes nearby, probably around 400-450 mm. per annum. Owing to the strong winds this goes less far to sustain plant life than it would on a bigger island. The mountains are not quite high enough to attract rainfall and their east-west orientation is, in this respect, a further handicap.

Soils are very weakly developed –tenuous rendzinas at most. There is not the tendency for cementation that is observed on other Greek islands.

Permanent settlement has now shrunk to the harbour town of Imborio, itself deserted, at the 1981 census, by 4 out of 5 of its people, which is largely a new foundation of the 19th century. The previous capital, or central settlement, Chorio, now abandoned, appears to be of medieval and early 18th century date, but incorporates many standing buildings and cisterns of the Hellenistic, Classical and Archaic periods. The peak above it is crowned with a castle of the Knights Hospitallers, adapted out of a Classical Greek (Rhodian) acropolis at the end of the 14th century.

This depopulated state of Chalki is not typical of its history. For at least 2,000 years it was evidently among the populous parts of Greece, probably because of the first-class harbour nearby at Alimnia. Sherds lie almost everywhere, and in parts of the plane are so abundant as to compose much of the soil. Most of the island should count as an archaeological site[6].

The earliest rural dwelling of Chalki is the kyfi (κύφη), an entirely stone structure typically 8×2.4 m, of rough corbelled construction. Each of the valleys has a hamlet of kyfes: other are scattered over the island, attached to isolated fields and terraces[7]. They are of unknown date: those in the Andramassos basin are associated with walls of apparently Archaic Greek construction. Many remained in use within living memory, as are similar stone built shelters in several of the Aegean islands.

There are no springs or rivers. The present (1986) scanty and more than brackish drinking-water supply, a result of over-pumping a minor water table, is among the worst in Greece. All the old settlements were elaborately provided with catchments and cisterns for storing rain. In Chorio the small village square, which is held up by Classical and Archaic retaining walls has at least seven cisterns beneath it. Four fresh-water wells are known on the island: one, of Ancient Greek or Roman date, is at the bottom of Chorio; another, which is named after Koukialis, the person who was in charge of it, was dug in the Pontamos valley in 1826, and two other are located behind the front line houses of Imborio,they are partly dug in the rock and provide small quantities of water that turns brackish during summer.

All the plains and basins, large and small, have been cultivated, and also such of the hillsides as have soil and are not too steep. They are surrounded and divided by dry-stone walls. Steeper slopes, even in remote places, are full of terraces (mostly of the braided type). Similar walls separate the cultivated areas from the hilltops which are the pasture areas. Long walls cross the island from coast to coast and partition it in five or six areas (the minoria, μινόρια[8]), they were alternatively cultivated or used as pastures during the triennial fallow[9]. A characteristic of the island, especially in the Pontamos valley, are «gardens”, circular stone enclosures without entrance, each enclosing two or three trees. All the stone construction is exceptionally massive and is evidently intended to get rid of stones. One stone-pile in Andramassos contains some 10,000 tons of stone behind and Archaic wall. Two smaller piles can be seen in Alimnia; they recall the cairns named hermakes (έρμακες) by Classical Sources[10]. These must be the work if a large population with nothing else to do during the idle periods of the Mediterranean annual cultivation cycle.

Since the World Was II famine there has been almost no agriculture on the island, but the grazing of goats and sheep continues. The island’s ecology is affected by these animals for some species of plant and dislike of others[11].

Modern Vegetation

Chalki can be divided into four types of terrain:

- Basins and plains with Older Fill (about 10% of the area).

- Hillsides with soil, mostly terraced and enwalled (35%).

- Rocky hillsides with little soil (45%).

- Cliffs inaccessible to goats (10%).

Basins and plains

The Pontamos valley below Chorio, sloping down to the coast towards Imborio, is filled with trees and luxuriant bushes, a dramatic contrast to the rest of the island. In part these are relics of cultivation.

The characteristic tree of Chalki is the terebinth, Pistacia terebinthus (agramithia, αγραμιθιά, αδραμμιθθιά), which is almost confined to this valley. Despite the general treelessness of the island these terebinths are among the biggest in Greece – spreading trees some 8 m high with trunks up to 50 cm thick, sometimes showing signs oof pollarding. They have a history of semi-domestication. Many of them are in «gardens», and property deeds of the nineteenth century mention terebinth trees, sometimes within walls, as assets[12]. However, there are wild terebinths in the nearby cliffs, and the tree is common in similar inaccessible places in the Peloponnese and Crete: there can be little doubt that it is native here, as in other islands of the Dodecanese. Terebinth is moderately palatable, and is often browsed and crippled by goats where they can get at it. It is accompanied by the woody climber Clematis cirrhosa.

Also especially abundant on Chalki is the small summer-deciduous leguminous tree Anagyris foetida, which grows under and among the terebinths, and sometimes reaches an exceptional size.

All the other trees are relics of orchards: almonds (often very large but generally in poor condition), figs, etc. There are no olive trees of great age, but many small ones, which appear to result from a last phase of cultivation after the island had begun to be depopulated[13]. Prickly-pear (the cactus Opuntia ficus-indica) was introduced in the last century (Eliades 1950 mentions extensive consumption of these frangosyka pears, p. 247-48) but has not prospered (see later)[14].

A notable wild plant is Euphorbia dendroindes (galatsida,γαλατσίδα), a big undershrub which loses its leaves in summer; its vivid «autumn» colours are a feature of Chalki in May[15].

The western part of the basins below Chorio, slopping down to Yali, is similar, but its orchards and gardens are less well preserved. In the past there were barley fields.

The other basins are flatter and consist mainly of former arable fields. They are more arid in appearance and are now covered with steppe and sparse phrygana, although some have Anagyris, and there is an exceptionally big almond tree[16] at Andramassos.

Hillsides

The present natural vegetation of Chalki consists of a mosaic of macchia (longos, λόγγος), gariga (frygana, φρύγανα), and steppe (livadia, λιβάδεια)[17]. As benefits an arid island, macchia is of very small extent and steppe predominates.

Macchia (vegetation composed of trees and shrubs) is almost confined to the Pefkia and Kania areas in the N.E. corner of Chalki. The two tree species, lentisk (Pistacia lentiscus) and juniper (Juniperus phoenicea), occupy different areas but with some overlap. They are reduced to wind-pruned bushes no more than 2 m high, covering up to half the ground, with phrygana and steppe between them. There are also a few junipers in tree form, with trunks up to 55 cm diameter, among old fields. Lentisk and juniper are accompanied by the miniature shrub Rhamnus lycioides subspecies oleoides, and by four carob trees (Ceratonia siliqua), relics of ancient cultivation.[18] Carob is a very palatable tree, and these individuals, from their multi-stemmed shape, evidently spent many years in shrub form before a period of reduced browsing allowed them to grow into trees. Lentisk is unpalatable and shows little sign of browsing, and the very distasteful juniper has not recently been browsed at all; these must be kept down to shrub form by drought and wind-pruning.

On the hill of Xypei east of the Castle, there are two prickly-oaks (Quercus coccifera), 3-4 m high, the only representatives of the commonest macchia tree of south Greece. They are multi-stemmed, with trunks up to 25 cm thick, arising from bitten-down bases 1.3 m across. They are probably several centuries old, and (like the carobs) spent most of their lives in the form of shrubs before relaxation of browsing let them grow up into small trees. Growth is slow because of wind-pruning.

Gariga (vegetation composed of phrygana undershrubs) is present everywhere, but is seldom continuous; more often the undershrubs are scattered among steppe and bare rock. There are several variants, ranging from the very dwarf, arid kind with dominant Thymus capitatus (thimari) through those with Sarcopoterium spinosum (afana), to relatively lush phrygana with Salvia triloba or Origanum onites (rigani). Teucrium polium is local. The only Cistus is Cistus incanus, abundant in a small area just outside the lentisk region.

Steppe is the most widespread set of plant communities, occupying pockets of soil and crevices in rocks. Perennial grasses such as Andropogon distachyos and Hyparrhenia hirta are abundant. Asphodelus microcarpus is locally dominant, especially near. The steppe is probably very rich in annual herbs, such as Trifolium stellatum and other legumes, Desmazeria rigida and other grasses, and Compositae such as Atractylis cancellata. Thistles are not so common as in some other Greek steppes, but include the curious Carlina tragacanthifolia, endemic to the east Aegean islands[19] and Scolymus hispanicus.

Cliffs

In the time at our disposal we were able to visit the two most easily accessible inland cliffs. On the way to Chorio is Egremmos, i.e. «Cliff» – a botanically rather rich series of north-facing crags, hung with many beautiful and curious plants. A S.E.-facing cliff overhangs a cave between Andramassos and Ayios Yannis Konda (at Maroni[20]).

Most of the cliff vegetation consists of specialised cliff plants. The magnificent Helichrysum orientalis is abundant on Egremmos, and include some huge old bushes; people use it as cut flowers[21]. The big yellow Centaures of orientalis flourishes on both cliffs. Other bizarre and robust herbs and undershrubs include the cliff salsify Scorzonera cretica, the tall knapweed Ptilostemon chamaepeuce (common also on Cretan cliffs) and Silene verbascifolia. The delicate flora of shady cliffs is represented by the little Campanula celsii and a white form of ivy-leafed toadflax (Cymbalaria muralis).

The most remarkable of these plants is a succulent shrubby pink, Dianthus probably rhodius, previously known from two cliffs in Rhodes[22], here it grows on the cave cliff.

In Greece and Crete many cliffs have another class of plants – those species (especially trees) which are confined to cliffs through severe browsing elsewhere[23]. This hardly occur here. The only frequent cliff tree is terebinth, which grows on Egremmos close to the Pontamos valley.

A speciality: Phoenix theofrasti

Nearly all the coast is steep-to, and we are not aware of any well marked coastal plant communities.

Chalki does, however, have one of the world’s rarest trees, the Cretan palm Phoenix theophrasti. By Pontamos bay there are two clumps of this tree (one of them female), growing on Older Fill and accompanied by the sea-stock Matthiola fructiculosa. Two small clumps (one male) grow on limestone rock at 30 m above sea level at the top of Imborio town and one or two tufts (including a male tree) in the town itself.

Until recently this palm was thought to be confined to four localities in Crete[24]. J. A. Moody and O. Rackham found it by the mouth of the Gaddara on the coast of Rhodes. There are three recent records near Marmaris in Turkey[25].

Comparison with other islands

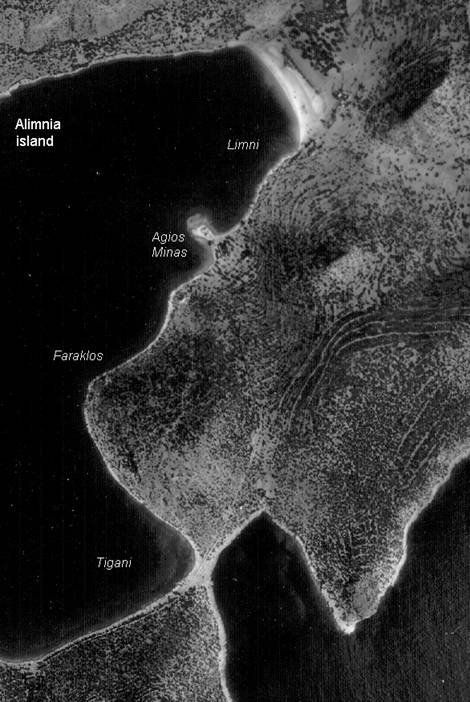

The neighbouring island of Alimnia, is also of limestone (but of a more brecciated and fissured texture than most of Chalki.) It is rather less mountainous, with extensive, formerly cultivate fields[26]. There is an abandoned hamlet around one of the monasteries and a small cultivated patch using brackish water from coastal wells. A hill top has a small Knight castle rebuilt on the remains of a Classical structure. Just under it there are clear traces of a hilltop settlement and blocks of cyclopean walls. Obsidian flakes and an arrowhead[27] lie on the surface.

On Alimnia, in contrast to Chalki, macchia is generally abundant, covering up to 30% of the ground. Lentisk and juniper form spreading bushes up to 6 m high on rocky hill-sides. The vegetation of Alimnia is like that on the part of Chalki nearest Alimnia (Kania), but is taller and less wind-pruned. The phrygana and steppe components are like those on Chalki; Salvia triloba is abundant. There is some coastal vegetation, with thickets of Vitex agnus-castus. Four palm-trees are introduced Phoenix canariensis. Abandoned olive trees are located on the N.E. slopes and on the coast facing Rhodes.

Rhodes (less than 10 km from Chalki) has great woods of pine and cypress; both have been present from ancient times, and are now rapidly increasing. Rhodes is much less arid than Chalki: it is bigger and higher and doubtless makes its own sometimes abundant, rainfall; it has soft limestones and other rocks which retain water. But the part of Rhodes nearest Chalki, including Mount Atavyros (1,215 m), is less wooded than most of the island. Tilos (20 km to the opposite direction) also has, or had, «great quantities of Cyprus trees»[28].

The small, uninhabited islands, all limestone, vary in vegetation. Makry (100 m high) between Rhodes and Alimnia, has low macchia of lentisk. Strongyli (72 m) appears to have juniper as well. Ayios Theodoros (Aï Thoros 101 m), between Chalki and Alimnia, has a less dense macchia. They are used as pastures and have cisterns and had churches and other built structures. The other, lower islets appear to have phrygana at most. It is also reported that women visit the islets to collect edible snails.

[Note 2009] As already indicated -note 6 above- Iliades (1950) provides the information that these surrounding islets were systematically used as seasonal pastures and their gariga (frygana) vegetation provided a small quantity of fuel. For this; the shepherds payed a rent to the Municipality[29]

What Limits the Modern Vegetation?

How far is the present desert-like landscape of Chalki due to the harsh environment, and how far to human activities? Of the four chief human influences on Greek vegetation, only grazing still operates. Cultivation has ceased since the 50’s and the plant cover is so tenuous that burning and woodcutting is hardly possible.

Chalki is said to be grazes by 3,000 goats and sheep (1988), which comes to about 80 animals per square km; this is a dense stocking for a dry island[30] The animals are only partly supervised: men go out daily to water the flocks, either out of brackish wells near the coast or from surviving cisterns inland. Between times the flocks move about and eat what ever they please, aggravating the effect of grazing on the vegetation. The present situation sharply contrast with past practice, when the animals were carefully confined in rangelands behind the minoria dry stone walls and only temporary allowed in fallow land.

Compared with other parts of Greece, grazing is rather severe. All palatable plants, including steppe grasses, are bitten right down, and the animals are forced to eat less palatable species such as Anagyris (an important browse in early summer), terebinth, and many under-shrubs. Lentisk (more distasteful than terebinth) is slightly attacked, but the very distasteful juniper shows no sign of damage.

It might be supposed that the difference of vegetation between Alimnia and Chalki result from different degrees of browsing, and that Alimnia is a model for what Chalki would have been if less browsed. However, there is no evidence for a difference in browsing history, and at present Alimnia is browsed slightly more severely than Chalki: the goats make a moderate attack on the lowest boughs of lentisk, though they do not touch juniper. Neither lentisk nor juniper is now limited by browsing on either islands, but they are not rapidly expanding. The part of Chalki on which they occur is just as exposed to flocks as the rest of the island. On Alimnia they are both abundant on the north-facing slope, even though this is more accessible to livestock than the precipitous south slope.

The effects of browsing would best be studied by means of exclosure experiments. Some of the walled «gardens» amount to such exclosures, and this was one of the purposes of building them. Most of them are now, through neglect, either dominated by big trees or accessible to goats through breaches; but there are few «gardens» on thin hillside soils which have no trees and which still have effective walls. In these the vegetation is phrygana of much the same species as those outside, but taller and denser. For example, in one such Euphorbia dendroides grows 1.8 m high (0.9 m outside), Anagyris 1.6 m (0,6 m outside), Salvia triloba 0.9 m (0.3 m outside). Thymus is absent inside the «gardens», doubtless because it is a weak competitor.

We infer that browsing is an important ecological influence; at some times of the year it affects even such a nasty-tasting plant as Euphorbia. But browsing, even when aggravated (as at present) by flocks roaming unsupervised determines the statue of the plant communities rather than their distribution. In general, the proportion of macchia, gariga, and steppe appear to be determined mainly by the moisture[31], and Chalki is no exception. Rainfall, though low and seasonal, is adequate for the growth of trees where there is enough soil to retain it, as in Pontamos valley. On most of the island, the vegetation is evidently limited by non-retentive rocks aggravating the shortage of rainfall. The drying and pruning effects of wind may also be critical: Pichler (1883) describes wind as limiting the growth of trees in north Carpathos nearby[32].

Ecological History

Chalki has a very poor written record. It never played any part in affairs of state, and travelers to Rhodes passed it by. The magnificent archaeology is mentioned by Gerola[33], and recently by Iliadis[34], Susini[35] and Antoniou[36]. It has never been fully surveyed.

Prehistoric times

Information kindly supplied by Dr. J. Volanakis, together with observations during our visit, indicates a substantial human presence during Early Bronze Age (3200-1900 B.C.[37]). There are extensive remains of a settlement around Alimnia Castle, such as obsidian flakes from Yali and a leaf-shaped arrowhead of what appears to be black obsidian from Melos[38]. Other sites, possibly of Early Cycladic II period (2800-2300 B.C.), were Chalki Castle, the Trachia isthmus, and Kefali. Scattered flakes and a core of obsidian, along with light gray translucent volcanic materials and of other hard stones suggest a territorial pattern of activities not unlike that at the beginning of this century (e.g. Pontamos, Andramassos, Pefkia, Agios Yannis, etc.).[39]

Classical period

Classical writers give a bare mention to the island: for example Strabo mentions a town, presumably at Chorio, and a harbour, along with a temple of Apollo[40]. The only scrap of ecological information – and that second hand – is Theophrastus, who says that in one place they get two crops of barley in a year[41].

Apart from obsidian finds, the standing remains and exceptionally dense scatters of sherds of coarse ware show that the island was thickly populated throughout Ancient Greek, Roman and early Byzantine times; examples range in date from Archaic walls at various places in Chorio, Ayios Yannis o Alarga to several Early Christian basilicas (Imborio, Pefkia and Limenaria at the N.E. corner, Koka by Ayios o Alarga). As in later ages, when Rhodes was prosperous, the population may well have been greater than could live off the land alone. Maritime trade is suggested by the safe anchorage of Alimnia where numerous dug-out dock channels can be readily seen.

The basins, and at least some of the hillsides, were evidently cultivates for centuries. Much of the work of moving stones and making fields appear to have been done by Classical times. For example, the Andramassos basin has several superimposed field patterns, some of them with field walls of polygonal masonry; another polygonal field-wall is still upstanding on the slope south of Pontamos, and similar structures are known from, photographs of Kefali.

Byzantine, Crusades and Turkish periods and since

The scanty written record of the area deals mainly in disasters: earthquakes, piracy (to which a small island would be exposed); evacuation of the island in drought, coinciding with Turkish wars, of the late fifteenth century[42]; and a massacre by a Venetian expedition in 1858.

The archaeological record indicates that the island continued to be cultivated and inhabited, though maybe not so densely as in Classical and Hellenistic times. A considerable population is suggested for example by early churches in remote places (e.g. Odhigitria, with a date-stone of A.D. 890) which imply seasonal gatherings of pilgrims. The islands also prospered under the Knight Hospitallers (1309-1522).

In the later Turkish period (since the 18th century) the fortunes of Chalki revived. Trading and sponge fishing flourished. The similar community on the island of Symi had a high reputation as divers[43], and Chalki too[44] lived by sponge-gathering. The population grew to a maximum of 3,200 in 1912. There was already a sizeable Chalkian colony trading sponges at Tarpon Springs (Florida). In that year prosperity came to a sudden end through Italy capturing the islands from Turkey in war. The trading links were broken, capital was taken to the U.S.A., the sponge-fishing journeys to Libya were interrupted and the population started melting away, declining by half every 20 to 25 years. Several of the half-built houses in Imborio result from these events. In March 1981 about 300 persons were enumerated as permanent residents, but because of Chalkians living in Rhodes many people are part-time residents and the population increases by 100 to 150 persons during late spring and summer. A further number of expatriates, besides tourists, also make short holiday visits[45].

Although the land cannot have been the main livelihood of most of the population, the field remains show that even the difficult terrain was fully used. This is confirmed by contracts and other documents of the years 1907-1923, indicating more fig-trees than now survive, arable land with barley, numerous oxen for ploughing, self-sufficiency in olive oil, and (even in 1908) vineyards inn five or six areas (Chalki Municipal Register). Vineyards were once quite abundant; they were probably destroyed by plylloxera in one of its late epidemic in the Aegean. Although Chalkians, from their visits to the United states, ought to have known how to deal with the pest, they never replaced the dead vines. Very narrow terraces, on the steep facing slopes of Mount Kapnikari and over the Andramassos valley, may be the sites of old vine plantations[46].

Plant Place Names[47]

From the recent past, some fourty place-names on Chalki are known that appear to be derived from plants[48]. Several place-names refer merely to common wild or cultivated plants, and since their origin cannot be dated earlier than the 19th century they do not add much to our knowledge: for example the many place-names involving sykos (σύκος) and other words for fig[49]. In this respect we may add information provided by Eliadis (1950: 247) who name seven different varieties of edible figs[50] Similar place-names include Kritharia (barley), Anginaries and Angynaros (Cynara), Krampia (Brassica ?), Kalamous (Calamus), Alimounta (presumably from halimus, Triplex halimus) and Triantafyllies (roses)[51]. Ampela, Akhladia, Kharoupia, and Rodia (as well as the local form Eroyia)[52] mean respectively vineyards, pear, carob and pomegranate trees.

Other place names deriving from common wild plants are: Askinaya (lentisk- skinaria) in the are Kania, Aroïnas (Anagyris foetida) a locality near Ayios Yannis; Alisfakia (a local word for Salvia triloba), Maroni (origanum)[53]. There are also three places bearing modern Greek names for «thistle»: Akkathi, Akantheroi and Katsias a Rhodian dialect name of Akanthus.

The prickly-oaks on Mount Xypei have generated the place-name Pramnaria (primnari, prinari, Quercus coccifera).

More significant are the place names that imply plants no longer there. We have already mentioned Pefkia (Πευκιά) as a place with different vegetation from the rest of the island. This place-name refers to pine, a do documents which mention places Pefkios (codex B 237/1892), Pefkoti (codex B 297/1895) and Stroïlia (the Pinus pinea, codex A 57/1884[54]). Pinus halepensis therefore grew on Chalki at some unknown date in or before the 19th century. Today the tree grows in Kania, close to Pefkia, but appears to have been introduced in the 1940’s; it is spreading into former arable land. On Alimnia, in the peninsula of Tigani, there are two acres of compact pine plantation which is even younger.

Other place-names indicate that trees were cultivated more widely than where they still survive. For example almond trees must have grown in the Amyglai area, in the N.W. of the island, and olive is the explanation of cape Elia and of another place-name in the mid-north, in an area from which it seems to have disappeared. Olives are still grown on Alimnia, near the coastal hill Elas (Ελάς)[55].

Among wild trees Finiki, indicates that Phoenix theophrasti once grew inland, to the north of its surviving locality[56]. Terebinth is indicated by a place-name near Chorio, where the tree still exists, and another in the north where it has probably disappeared.

Building timbers[57]

The oldest extant timber on the island is probably a door-lintel in the medieval castle; it is of deciduous oak reused from some other purpose[58].

Houses in Chorio are of two kinds, both one-storeyed, with flat roofs of earth supported by timbers. Houses of the “Dodecanesian” type are spanned from end to end by one great beam supporting the common joists; over this are laid short lengths of timber or planks which carry the earthen roof[59]. All the timbers are cypress, Cypressus sempervirens. The axial beam is typically 10 m long by 30 cm square at one end, tapering towards the other end; often it is in two separated lengths scarfed together and supported by a central post. The second, more primitive and probably older, house type has no axial beam but is spanned instead from side to side by about ten cypress trunks, which are rather less quality and measure some 4.5 m long by 20-25 cm square at the big end.

Apart perhaps, from a few lengths of olive as lintels, there is no evidence that the Chalkians ever used timber of local origin. Instead they brought cypress, the nearest source being the interior of Rhodes. There is no sign of economy in timber: they used cypress even for the infill between joists, which elsewhere can be juniper of even vine-prunings; they did not use Rhodian pine which would have been nearer and probably cheaper; and they incurred the labour of manhandling huge beams up to Chorio, when a small change of design would have called for much smaller timbers.

Building contracts of 1908-1909 tell us that there were specialised carpenters (possibly also shipbuilders), and show that the lavish use of timber still continued. People spent much more on carpentry than on masonry and cisterns. The timbers of Chorio are probably older than the urban houses of Imborio, where sources mention one-storey houses with rounded vaults (tholoi, θόλοι). We may infer that marine trading activities may account for the imported timbers. Imborio carpenters reused ship planks. Similarly, Marseilles and British tiles that are found on the island must have been used to ballast returning ships.

Recent changes

For the last hundred years we have three sources: the evidence of the plants themselves, the photographs of castles and antiquities taken in ca. 1913 by G. Gerola and local records mentioning cultivated properties.

On Alimnia macchia has increased but the two species have behaved differently. Gerola’s photographs of the castle show that all the lentisk bushes now visible in his views were already there in 1913; some are bigger and some smaller, but the most conspicuous have hardly changed in 75 years. Junipers have increased and new plants can be seen on the Tigani peninsula. The photographs are probably typical of the island. Most if the lentisks on Alimnia are at least a century old, except for those few that have grown on fields abandoned 15 years ago (c. 1970). The junipers, some of which can be dated by annual rings, are mostly younger – between 50 to 100 years old. There are few young junipers in the central part of Alimnia, but the species does not invade ex-cultivation.

On Chalki the juniper and lentisk bushes may well be of similar ages to those of Alimnia. At least one of the juniper trees in fields, however, is known from annual rings to date from the late 18th century. Both species occasionally invade ex-arable land, but otherwise show no tendency to advance or retreat. We have seen that the few carobs and prickly-oaks are witnesses to a period of reduced browsing, possibly in the 1930’s or 1940’s. These more palatable trees would respond more strongly than lentisk or juniper. Manuscript notes taken in 1938 indicate a smaller number of sheep and goats on Chalki, and comparatively large number grazing on Alimnia and on the islets.

Terebinths and other plants in cultivated areas have now grown much bigger than they would have been when the cultivation was maintained. A large percentage of the fig trees known to have existed in the 1920’s seem to have disappeared or turned into multi-stemmed bushes by cutting. Gerola’s photograph of Chorio shows that the inhabited village was much less tree’d than the deserted village is now. However, the biggest of the fig-trees has died back severely since 1913; and thickets and hedges of prickly-pear, prominent in Gerola’ scene, are now largely represented by the monstrous carcasses of dead cacti. Similarly, Opuntia is no longer visible in the walled «gardens» by the Pontamos road where their presence is mentioned, along with fig trees in 1908.

Even the phrygana may have increase: Gerola’s photograph shows that the luxuriant growth of Origanum, now around the castle, was not there in 1913.

Conclusion

The early vegetation history of south Greece, based mainly on pollen analysis, tells of an era before the Bronze Age when the climate was less arid than it is now; when, for instance, northern trees such as lime were not uncommon even in Crete[60] None of our evidence for Chalki goes back so far; we are concerned with an era in which the climate has not been very different from the present. The evidence that we have is of long periods of cultivation, in more or less the present environment, by a large and hard-marking population. This need not have been quite continuous. There is some evidence of lesser climatic fluctuations in Greek climatic history[61], and a small island without springs would be especially at risk from drought, even from a single dry year in which the cisterns did not fill, as happened in the 1470’s[62].

Fluctuations in human population will have affected the cultivated area, but not necessarily the landscape at large. Alimnia shows that goats can still graze an island even if people no longer live there. Indeed grazing may be more severe, because unsupervised, in a depopulated place. This seems to have occurred on most of the small islands of the Aegean during times of insecurity, when a residual number of people living in «kyfes» and underground shelters survived mainly from pastoral resources[63].

Wee have no evidence that Chalki had woodland or timber trees. In the Cyclades the local architecture is adapted to making the best use of short and scanty local trees[64]. Not so here: the «kyfe» is a kind of house, which (like the kathoikia or stavli[65] of Kea) uses no timber at all, while the Chorio houses make rather lavish use of imported timber.

What would be the natural vegetation of Chalki?

The original natural vegetation will probably never be known, except to the vague degree to which it is possible to extrapolate from parts of Greece in which fossil pollen preserves a record of past vegetation. For a small island such as Chalki an essential piece of information is missing, namely wild mammals, if any, it once had. An island that never had mammals, for example, will presumably have a different vegetation history from one that had herbivorous but no carnivores. It is more reasonable to ask what the present vegetation would be if Chalki had never been inhabited by men or domestic animals[66].

Pollen analyses agree in showing that the pre-agricultural vegetation of Greece was a mosaic of evergreen trees and steppe, with deciduous trees abundant probably on the deeper, now cultivated, soils. Chalki, as a dry island, ought to have had more than its share of steppe, especially after the climatic change. There can be little doubt that the three major vegetation types of pre-Neolithic Greece are still recognizable on Chalki today in the form of the small amount of macchia, the large area of steppe, and the terebinth area.

Cliffs provide a clue as to whether trees were ever abundant on the island. If prickly-oak, juniper, or terebinth had ever been widespread, they ought to survive (as they do for instance in Crete) in inaccessible places well outside their present limits. They do not.

We infer that the natural vegetation of Chalki in the present climate is not much limited by browsing. Without goats it would probably consist of taller and lusher versions of the present plant communities: steppe and phrygana on most of the hillsides, terebinth woodlands (possibly with other deciduous trees) on the deepest soils, and macchia in the north-east corner. Evergreen trees, such as prickly-oak, would be no more than very thinly scattered over the island as a whole.

Pine is an imponderable. Woods of Pinus halepensis replace macchia in some parts of Greece but are quite absent from others, in an apparently unsystematic way. Pinus brutia, the pine of Rhodes, is similarly unpredictable in Crete. Historical studies and pollen analysis show that pine has come and gone unpredictably in the past. Why pine should have died out from Pefkia is uncertain. It is a gregarious tree, always forming woods, and probably dependent in some ways on fire; a small island population might die out through some mishap, such as burning at the wrong stage of the tree’s life cycle, or not burning at all.

Is there any connection with erosion?

Chalki is a very eroded island. It is clear that, as in most of the rest of Greece, most of the erosion took place in the Pleistocene for reasons unconnected with human activity. Much of the eroded material was swept into the sea; some of it was to make cultivation possible by forming Older Fill in the plains.

The later history of erosion on the island will not be fully understood until there is an archaeological survey, but some inferences can be drawn. Erosion during historic times produces the deposits collectively known as Younger Fill; these are often paler and grayer than Older Fill, and contain sherds. From the vast quantity of sherds on Chalki there should be no difficulty in recognising or dating Younger Fill. It is certainly not of general occurrence.

There is small area of Younger Fill, up to 3 m thick, on and immediately below the site of Chorio. Where it has piled up against the back wall of the principal church (Panagia), it can be seen to be more recent than the older part of the church – a Classical Greek building much repaired in Byzantine or Crusade times. It must be older than the eighteenth century, since the more recent houses in Chorio are built on it.

There has apparently been some erosion in the Andramassos basin, on the slopes of which are faint traces of ancient field systems now devoid of soil. This can be no later than the Roman period, from the abundant sherds and other evidence of very long cultivation of the present soil surface. More exact dating could be provided by studying the base of the 10,000 tons cairn and of the archaic wall enclosing it.

With these exceptions, there has not been much erosion since the making of the present terraces and field enclosures. All of these, though long disused, are capable of restoration; they have been abandoned for socio-economic and political reasons, not because their soil has gone.

Is erosion active at present?

There are three tests allowing us to answer this question: on an eroding slope, bushes are left perched on pedestals. Material piles up to form banks (lynchets) against cross-slope walls and other obstacles. Rock exposed by receding soil have a smooth, pale surface very different from the patina of weathering and lichens on rocks that have long projected above the surface. In most of the island there are no empedestalled bushes, little or no lynchetting, and little unpatinated rock. Abandoned terraces develop breaches which gradually subside back to the original angle of rest.

We conclude that the Pleistocene erosion took much of Chalki down to the bed rock, so that there is little scope for further erosion. What soft material remains is not very erodible. There have been episodes or erosion in historic times of small extent and of unknown cause. At present, despite the sparse vegetation, erosion appears to be very slight, except in two areas: (i) around Imborio town, where goat-treading is very \severe and there is some soil to be lost; (ii) in the Pontamos valley, where there is a big gulley, of unknown date, cut into Older Fill and still active in places; it still washes small amounts of soil into the little plain at the bottom of the valley.

The Future

If Chalki looks like a desert island, this can be ascribed more to an unusually harsh environment of climate and rock than to severe human mismanagement. Desertification, if we can call it that, took place mainly through the general drying of the climate of south Greece in the Bronze Age or earlier. Since then, there is no reason to suppose that the natural vegetation has ever been altogether different from what it is now. Much of the island has been cultivated, but with great effort. Cultivation has been abandoned, not for any cause that can be called desertification, but because there are no longer inhabitants willing to continue the effort.

In the last century Chalki and Alimnia were more desert-like than they are now. This is an example of the «de-desertification» which has happened in many parts of south Greece from similar causes[67]. In Chalki the change has been relatively slight because of the climate, but is likely to continue.

At present the environment of Chalki appears to be stable and is not threatened. Large-scale tourist development is impracticable because of the meagre water supply and the lack of accessible beaches. There is no sign of rapid change in vegetation or soils. The remaining inhabitants seem not to be discontented with their island, especially since substantial public works have been initiated including the rehabilitation of numerous derelict houses. There is a prospect of encouraging visits by small number of discriminating tourists who will value Chalki for its peculiar character, traditions and antiquities. (Facilities for some 300 visitors and a Conference centre have been developed in the beginning of the 1990’s). The future of the landscape should therefore be seen in terms of conservation rather than restoration. It would be pointless, and destructive of the island’s character, to try to «restore» it to a Rhodes like luxuriance of vegetation which probably never existed on Chalki.

The essential dates on the environment of Chalki are lacking, and in their absence no management work can be more than experimental. Priority should be given to setting up a simple weather station recording temperature and rainfall. Removing or controlling flocks has been proposed. It is doubtful whether any benefit would result, but this can only be known for certain by maintaining and recording experimental exclosures over several years. Without these and other similar data, it would be easy to spend money on «remedial» work whose consequences may be nil or counterproductive.

Introducing trees, especially Pinus halepensis, should be done cautiously if at all: the result could be, at one extreme adding to the many neglected and stunted plantations which dot the Greek islands; or, at the other extreme, the trees might multiply out of control, cover parts of the island and destroy its special character, and generate a great fire every few years.

The people of Chalki should be encouraged to appreciate and protect their botanical treasures, the cliff plants and the Cretan palm. The survival of the latter is precarious; the remaining clumps need protection either from damage or from falling into the sea.

A modest amount of work could be done on conserving the cultural landscape. To restore the agriculture (except on a very small scale, almost as museum demonstration) would be an impracticably large task. However, a special feature of Chalki is the «gardens» around and below Chorio, which are all the more delightful because of their setting between stern barren mountains. It should be possible to rescue some of them from dereliction and to include the whole area in any scheme for understanding and presenting the island’s antiquities. Similarly sensitive areas are the Andramassos valley, the high grounds around the monastery of Ayios Yannis, Kefali and parts of Alimnia.

The trees and plants are not mere decoration, but are part of the island’s antiquities and traditions. The object must be, not to introduce species from the outside which have no meaning in Chalki, but to encourage and perpetuate the plants – terebinth, euphorbia, and others – which along with the domestic species (figs, olives, almonds, vines) are part of the island’s history and distinguish it from other places in the Aegean.

Texts and Documents

Οι Αρχαίοι Νεώσοικοι της Αλιμνιάς (Νικόλας Βερνίκος 2008)

Τόσο μέσα όσο και έξω από τον κυρίως κόλπο της Αλιμνιάς συναντούμε στην παραλία έναν μεγάλο αριθμό από σκαμμένα αυλάκια νεώσοικοι (slipways, slip ramps) που χρησιμοποιούντο για να σέρνουν τα πλοία στη στεριά (πρβλ. τα αντίστοιχο αυλάκια που υπάρχουν στην παραλία του Δρυού της Πάρου[68], όπως και 3-4 άλλα στα Πηγάδια της Καρπάθου που αποτυπώσαμε με την βοήθεια του συναδέλφου Μανώλη Μελά από το Δημοκρίτειο Πανεπιστήμιο Θράκης).

Έξω από τον εσωτερικό κόλπο, δεξιά είναι ένας σχετικά τετράγωνος όρμος που δεν ονομάζεται στον χάρτη και βλέπει Ν-Α (στο σορόκο). Εκεί έχουμε έναν στενό λαιμό που ενώνει τη σημερινή χερσόνησο Τηγάνι (Τηγάνι σημειώνεται και στον χάρτη του Ηλιάδη) με την κυρίως Αλιμνιά. Από τον λαιμό αυτόν περνάει – όπως φαίνεται στην αεροφωτογραφία – ο δρόμος που ένωνε την ιταλική στρατιωτική εγκατάσταση με το ύψωμα που είναι πάνω από τον οικισμό του νησιού. Πριν από την κορυφή του πρώτου λόφου τα μονοπάτια – και μαζί τους οι παλιοί τράφοι διακλαδίζονται δεξιά (Α) προς τον κόλπο «Emporio-Ημποριός» και το capo Viti. Στο Εμπορίο (Ημποριό) αυτό επεσήμανε ο Ι. Βολανάκης τρίκλιτη βασιλική στο επίπεδο της θάλασσας.

Από το ύψωμα το μονοπάτι και οι αναβαθμίδες στρίβουν αριστερά (Δυτικά) – ακριβώς πάνω από το μοναστήρι του Αγίου Μηνά που είναι μέσα στον κόλπο- κυκλικά πάνω στην πλαγιά που είχε καλλιεργημένα δέντρα και οδηγεί στον οικισμό.

Ο ιταλικός χάρτης δείχνει εξ άλλου να υπάρχει και ένα μονοπάτι που πηγαίνει απ’ ευθείας από τον οικισμό στον κόλπο Εμποριό. Από τον οικισμό πάντως δεν φαίνεται το Εμποριό, όπως δεν φαίνεται και από το Καστέλλο γιατί παρεμβάλλεται λόφος ύφους 76 μέτρων. Τόσο όμως η ονομασία «εμποριό/ημποριό» όσο και τα αρχαιολογικά ευρήματα που υπάρχουν στον μικρό αυτόν όρμο που διαθέτει αμμουδιά και μοιάζει να είχε και δύο κτίσματα, δηλώνουν ότι όλα τα αγκυροβόλια της Αλιμνιάς χρησιμοποιούντο και χρησιμοποιήθηκαν.

Νεώρια (νεωσοίκους) εμείς είδαμε όταν σταθήκαμε στον λαιμό σε όλη την εσωτερική περίμετρο του έξω όρμου, όπως και σε όλη την παραλιακή ζώνη που πλαισιώνει δεξιά και αριστερά το μοναστήρι του Αγίου Μηνά, που προβάλλει σαν μικρό κεφάλι μέσα στη θάλασσα. Να σημειωθεί ότι ο κόλπος έχει αρκετό βάθος (16-12 πόδια) και το μικρό ρυμουλκό πλησίασε πολύ κοντά στην παραλία στον μυχό όπου είναι το άλλο μοναστήρι του Αϊ Γιώργη.

Στο τεύχος εξ άλλου των Les Dossiers d’Archéologie; La Marine Antique, no. 183 Juin 1993, o David Blackman δημοσιεύει στη σελίδα 38 μια φωτογραφία παραλίας όπου φαίνονται στο επίπεδο της θάλασσας υπολείμματα αρχαίων νεωρίων σκαμμένων μέσα στο βράχο. Πρόκειται για φαρδιά σκαριά (larges cales) που ο Blackman υποθέτει πως στεγάζονταν από διπλά υπόστεγα. Η τοποθεσία λέγεται πως είναι «ένα νησί στα ανοικτά της Ρόδου», πρόκειται όμως χωρίς άλλο για ακτή της Αλιμνιάς στο εσωτερικό του κόλπου.

Ας σημειωθεί ότι με εξαίρεση την αμμουδιά του μυχού, μπροστά στο κλειστό χωράφι και γύρω από τον Αϊ Μηνά η παραλία προς τη χερσόνησο Τηγάνι και το Τηγάνι είναι βραχώδης και ανεβαίνει αρκετά γρήγορα στη γραμμή των 10 μέτρων. Αυτό φαίνεται άλλωστε και στην φωτογραφία του Blackwell. Ταυτόχρονα, όπως είπαμε, ο βυθός κατεβαίνει απότομα – με εξαίρεση και πάλι τον περίγυρο του Αγίου Μηνά, που και στην αεροφωτογραφία δείχνει ρηχός.

Αυτό σημαίνει ότι τυχόν εγκαταστάσεις με υπόστεγα, κατά μήκος της ακτής θα ήσαν παρατεταγμένα κατά μήκος της ακτής και από τις στέγες τους θα μπορούσαν οι άνθρωποι να περάσουν εύκολα στην πλαγιά ή θα υπήρχε συνεχόμενος τείχος πίσω από τον οποίο θα είχαν κατασκευάσει πέρασμα και σύστημα αποχέτευσης για να μην μαζεύονται νερά. Κάτι τέτοιο υπήρχε στον Πειραιά σύμφωνα με το άρθρο των Ι.Χ. Δραγάτση και W. Doerpfeld, «Έκθεσις περί των εν Πειραιεί ανασκαφών», Πρακτικα Α.Ε., 1885, σ. 63-68 που περιέγραψαν τους Νεωσοίκους του Πειραιά. Στην περίπτωση πάντως της Αλιμνιάς δεν είδαμε να υπάρχουν ίχνη τειχισμάτων. Θα πρέπει λοιπόν τα υπόστεγα να ήσαν πιο πρόχειρα, ή να έφυγαν ακόμα και οι πέτρες των θεμελίων που ακουμπούσαν στην πλαγιά.

Αξίζει να σημειώσουμε ότι οι ιταλοί αρχαιολόγοι που ήρθαν αρκετές φορές στην Αλιμνιά και που έπρεπε να είχαν απαραίτητα την άδεια των ιταλικών ναυτικών αρχών για να επισπευτούν το νησί δεν έχουν πει λέξη για τα νεώρια. Όσο για το ιταλικό ναυτικό επαναλαμβάνουμε ότι μέχρι το τέλος του Β’ πολέμου είχε μόνιμη βάση μέσα στον κόλπο, όπου βρίσκεται και ακόμα και ένα μεγάλος στρατώνας που χρησίμευσε και στους Γερμανούς.

Ας σημειώσουμε ότι ο Blackwell αναφέρει ορισμένα σκαφτά νεώρια, σύρτες, που έχουν βρεθεί στην ευρύτερη περιοχή του Ν Αιγαίου που μας ενδιαφέρει. Αυτά βρίσκονται:

1.- ένα κοντά στο λιμάνι της Σητείας, έχει μήκος 30 μέτρα και μεγάλη κατωφέρεια.

2.- ένα άλλο στα Μάταλα που φαίνεται πως είναι σκαμμένο στο βράχο, (με διαστάσεις 3,80-4,50 μ. και περί τα 30 μ μήκος, όπως άλλωστε και οι τρεις σύρτες του Ρεθύμνου) [69].

3.- στα ερείπια των εγκαταστάσεων του αρχαίου λιμένος στο Μανδράκι της Ρόδου (σύμφωνα με γερμανική ανασκαφή που είναι ανέκδοτη μέχρι σήμερα).

4.- στα Φαλάσαρνα της Κρήτης όπου φαίνεται ότι υπήρξαν υπόστεγα με άνοιγμα 4 μέτρων.

5.- στην Κω, όπου στο εσωτερικό του υπόστεγου υπάρχουν δυο σειρές από εγκοπές, διατεταγμένες ανά δύο, η μια απέναντι από την άλλη, πάνω από τους θεμέλιους λίθους. Στις εγκοπές αυτές πρέπει να έμπαιναν τραβέρσες, που ακουμπούσαν πάνω στο επίπεδο ολίσθησης.

Ο Coates πιστεύει πως τραβούσαν τα πλοία στη στεριά πάνω σε γρασαρισμένα επίπεδα φτιαγμένα με δοκάρια μέσα σε πέτρινα αυλάκια (Καρπαθ. σιρσίνια) βλ. Coates J.H. «Hauling a trireme up a slipway and up a beach», in J.T.Shaw (ed.) HN Ship Olympias: a Reconstructed Trireme, Oxford 1993.

Ακόμα πρέπει να προσθέσουμε ότι στενά πλοία είχε η Ρόδος. Ο Blackwell μάλιστα σημειώνει ό,τι τα ημιόλια και τα τριημιόλια ήσαν κατ’ εξοχήν ροδίτικα σκάφη. Ακόμα θα προσθέσουμε ότι η Marguerite Yon ερευνά από το 1989 τους νεωσοίκους του λιμανιού του Κιτίου στη Κύπρο.

Στο ίδιο εξ άλλου τεύχος Marine Antique, o L. Basch αναφέρει ότι οι αναλογίες του πλοίου που είχε αναθέσει ο Αντίγονος Γονατάς στη Σαμοθράκης πρέπει να ήταν 1/5, ενώ οι αναλογίες των τριήρεων της Αθήνας πρέπει να πλησίαζαν το 1/7 (10,37μ/ 69,40). Έχουμε τέλος και μερικά γιγαντιαία σκάφη των Λαγιδών όπως και τον Λεοντοφόρο του Λυσίμαχου (110×10 μ) που κληρονόμησε ο Πτολεμαίος Β’ και τα Ίσθμια του Αντιγ. Γονατά (70×20 μ.) που αντέγραψε ο Καλιγούλας κατασκευάζοντας τα πλοία της λίμνης Νένι.

Αλιμνιά

Υπάρχουν δύο λιθοσωροί στην Αλιμνιά.

Οι λιθοσωροί της Αλιμνιάς πλαισιώνουν την καλλιεργημένη ζώνη δίπλα στον οικισμό, στο μονοπάτι που οδηγεί προς το Καστέλο. Υπάρχει επίσης και ένας μικρός ακατέργαστος ορθόλιθος, είχαμε σημειώσει στο ημερολόγιο της επίσκεψης: «στο Ταφιό ο ορθόλιθος».

Σύμφωνα με τον Ηλιάδη (σ. 234) οι σωροί από χαλίκια ή πέτρες λέγονται χοχλακιές.

Στην Κάσο οι σωροί αυτοί από πέτρες ονομάζονται χοχλακούρες (η χοχλακούρα) και χοχλατσιά. Στις Καρούμες[70] της ανατολικής Κρήτης έχουμε την κοιλάδα Χοχλακιές, όπου αναφέρεται παρουσία λιθοσωρών.

Υποθέτουμε πως κάτι το αντίστοιχο περιγράφουν οι αρχαίες λέξεις λίθαξ και έρμαξ. Βλέπε: Λεξικό Liddell-Scott: λίθαξ-λίθακος, «μή πως μ’εκβαίνοντα βάλη λίθακι ποτι πέτρη κύμα μέγ’ αρπάξαν.» Οδ. 5.415

(η) έρμαξ-έρμακος (έρμα) heap of stones, cairn, Nic. Th. 150 [Νικανδρος επικός 2 αι. πΧ, Theriaca]; Λίθακες τε και έρμακες, Epic. in Arch.Pap. 7.10. (Πρβλ. επίσης Suida Κάχληκες: λίθακες εν τοις ύδασι.)

Ο Αδαμάντιος Σάμψων (1957« Η νεολιθική περίοδος στα Δωδεκάνησα». Αρχαιολογικό Δελτίο 35, Αθήνα).αναφέρεται στο άρθρο αυτό και στην Αλιμνιά, στις σελίδες 79-85 και 105-107. Στη σελίδα 106 απαριθμούνται οι θέσεις Κάστρο, Ποντικοβουνάρα, Εμποριό, Άγιος Μηνάς. Ο Σάμψων σημειώνει την παρουσία εργαλείων απο οψιανό της νήσου Γυαλί. Βλέπε επίσης την εικόνα του αντικειμένου 137α (αριθμ. 114) μύτη από οψιανό Γυαλιού που θα μπορούσε να είναι μύτη βέλους ή καμακιού (harpoon).

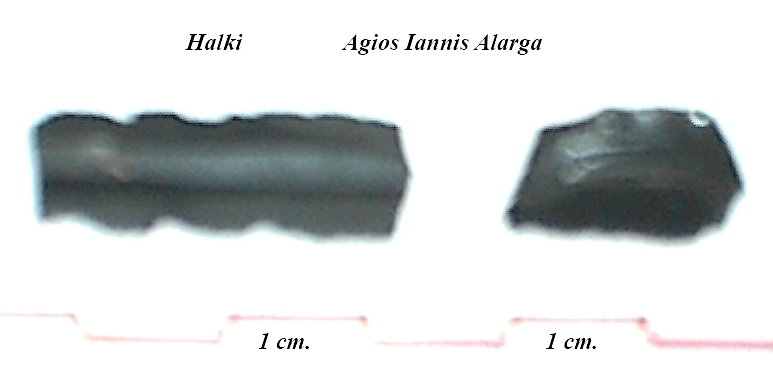

Στη διάρκεια επίσκεψης μας είδαμε οψιανούς απροσδιόριστης προέλευσης τόσο στο λαιμό του εσωτερικού όρμου Τηγάνι και κάτω από τη θέση Τοίχος, όσο και στον προϊστορικό οικισμό που βρίσκεται κάτω από το Κάστρο της Αλιμνιάς. Χαρακτηρίζουμε τους οψιανούς αυτούς «απροσδιόριστης προέλευσης» επειδή μπορούμε με βεβαιότητα να πούμε ότι δεν προέρχονται από το Γυαλί, αλλά ενδέχεται εκτός από την Μήλο να έφταναν οψιανοί και από άλλες προελεύσεις. Τα διάφορα επιφανειακά ευρήματα κινηματογραφήθηκαν, πάντως, με δική μας υπόδειξη από τα δύο άτομα που συνόδευαν την πρώην νομάρχη Πιερίας κα. Μαρία Αρσένη η οποία τότε είχε αναλάβει τον οικονομικό εξορθολογισμό του αναπτυξιακού προγράμματος της Χάλκης. Είναι άγνωστο τι έγινε με τις εικόνες που φωτογράφησαν, τότε, οι δύο νέοι συνοδοί της κας. Αρσένη.

Στη διάρκεια επίσκεψης στην Αλιμνιά και παρουσία των Χρ. Παπαχριστοδούλου, Ι. Βολανάκη, και Ν. Μουτσόπουλου (1991) βρέθηκε μια ακέραια αιχμή βέλους από οψιανό της Μύλου στα θεμέλια κατοικίας μέσα στον οικισμό, που αφέθηκε στη θέση της. Οψιανό άλλης προέλευσης – πιθανότατα της Μήλου, συναντήσαμε επιφανειακά στην περιοχή του Αη Γιάννη τ’ Αλάργα, ένδειξη ότι στα μέρη της Κοίλας και του Αη Γιάννη υπήρχε ανθρώπινη παρουσία, άρα και καλλιεργητική δραστηριότητα από την εποχή των λίθινων εργαλείων.

Παραθέτουμε την εικόνα μιας λεπίδας που εντόπισε ο O. Rackham στο εσωτερικό της Χάλκης.

Πρέπει να επισημάνουμε πως αρχαιολογική έρευνα στον προϊστορικό οικισμός της Αλιμνιάς δεν έχει γίνει και η επιφανειακή έρευνα του Αδ. Σάμψων δεν επαρκεί, ιδίως μετά τις νέες ανακαλύψεις προϊστορικών οικισμών των Κυκλάδων.

Κείμενα του Ηλιάδη

Iliadis (1950)

«Την Χάλκην, …την έχουν μοιράσει σε δύο Γεωργικάς πεεριφερείας για να γίνεται κατ’ έτος εναλλάξ η σπορά πότε πάνω (Πάνω Σπορά), πότε κάτω (Κάτω Σπορά), δια δύο λόγους, την αγρανάπαυσιν, και δεύτερον για να βόσκονται κα τα αιγοπρόβατα εις την περιφέρειαν που δεν είναι σπαρμένη την χρονιάν εκείνην. Όσον αφορά δε τα χονδρά ζώα έχουν ξεχωρίσει μίαν άλλην Αγροτικήν περιφέρειαν, την Χερσόνησον της Τραχειάς, εις την οποίαν αφήνουν ελεύθερα τα ζώα προς βοσκήν σε ορισμένην εποχήν του έτους που δεν τα χρειάζονται πλέον δια γεωργικάς εργασίας.» (σ. 251)

Iliadis (1950)

«Οι σαλαές της Ατρακούσας ….

Το ως άνω νησίν η Ατρακούσα έχει πάνω πολλές σαλαές (σαλιγκάρια) και επήγαιναν τα πρώτα χρόνια και εμάζευαν και εφέρναν τας και τας επουλούσαν εις την Χάλκην.

Μιαν φοράν επή(γ)αν πάλιν πάνω στην Ατρακούσαν Χαλκίτισσες να μα(ζ)έψουν σαλαές και επήραν μαζίν των και μερικά κορίτισια, και έκαμναν δύο τρεις μέρες πάνω στο Νησί και εκοιμούντο μέσα στα κελλιά που έχει το εκκλησάκι του Άϊ Αντώνη. …» (σ. 146)

Salname Cezair-i Bahri-i Sefid

Bilingual Ottoman Almanac- Vilayet Salnamesi- of the (Eastern) Aegean Islands (1883-87)

Απόσπασμα από τα Δίγλωσσα Οθωμανικά Ημερολόγια του Αρχιπελάγους

Salname Cezair–i Bahri–i Sefid (έτη Εγίρας 1301/1883-84 και 1304/1886-87.

Ελληνικό κείμενο – original Greek text

«Εκτός τούτων, προς δυσμάς της Ρόδου, υπάρχει ικανός αριθμός νήσων και νησιδίων ων περιφημότεραι είναι η Κάρκη και η Λημνιούσα[71], κείμεναι μεταξύ της Επισκοπής και της Ρόδου και απέχουσι της τελευταίας κατά 6 μίλια. Πλησίων αυτών υπάρχουσι διεσπαρμένα διάφορα νησίδια δια μέσου των οποίων τα πλοιάρια δύνανται να διέλθωσιν ακινδύνως.

Επαρχία Χάλκης.

Μαχμούτ Ραχμή εφένδης, έπαρχος.

Το 1304 Ε. έπαρχος Χάλκης ήταν ο Σακίρ εφέντης.

Μέλη του ειρηνοδικείου [Χάλκης].

Παναγιώτης Φηνδηκλής αγάς.

Κανέλος Πιπίνος αγάς.

Ανάργυρος Πέρης αγάς.

Αντώνιος Διαμαντής αγάς.

Τρία χρόνια αργότερα, σύμφωνα με το Ημερολόγιο του 1304 (1886-87) το «Πρωτοδικείο Χάλκης» αποτελείται από τον Μεχμέτ εφένδη πρόεδρο, και τους Ελευθέριο Κανάκη εφένδη, Ιωάννη Αλεξιάδη εφένδη, Βασιλάκη εφένδη, Ιβραχήμ εφένδη και Χασάν εφένδη, μέλη.

Τελωνείο και χωροφυλακή.]

Τελωνείον [Χάλκης].

Ιβραχήμ Εδχέμ εφένδης, τελώνης.

Χωροφυλακή [Χάλκης].

1 δεκανεύς μετά 5 χωροφυλάκων.

Περιγραφή επαρχίας Χάλκης

Η νήσος Χάλκη έχει 550 οικίας, πληθυσμόν 3.500 ατόμων και 20 εργαστήρια και παράγει σίτον, κριθήν, σύκα, σταφύλια και αμύγδαλα.

Το 1304 Ε (1886-87) φαίνεται να έχουμε μείωση πληθυσμού σε «2.013 ψυχάς», παράγονται «εν ολιγότητι» τα ίδια προϊόντα και σημειώνεται ότι «Οι πλείστοι των κατοίκων είναι σπογγαλιευταί.»

Notes

[1] Professor Dr. Oliver Rackham (OBE), is a Fellow of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. He is also Keeper of the College Silver. An acknowledged authority on the British countryside especially trees, woodlands and wood pasture. Since the 1990s he is studying the Aegean and Mediterranean ecology and the historical development of vegetation, forests, trees, and woodlands in various parts of the world. Rackham has written a number of well-known books, including The History of the Countryside (1986), one on Hatfield Forest, and on Crete (Greece 1987). In 1998 he was awarded the OBE.

[2] See ref.: Observations on the Historical Ecology of Santorini — The Thera …

5 Apr 2006 … As I remarked at the previous Congress, the flora of Santorini – that is, … comparable to Chalki of Rhodes (Rackham and Vernicos, … and from two sites in the Akrotiri on the north coast of Crete (Moody et al., forthcoming). www.therafoundation.org/articles/environmentflorafauna/

[3] Extensive Neolithic findings in various places on Chalki, along with the prehistoric settlement on Alimnia prove that these islands were exploited at a very early stage.

[4] Cf. lat. Emporium> Imporio.

[5] See ref.: Observations on the Historical Ecology of Santorini — The Thera 5 Apr 2006 … As I remarked at the previous Congress, the flora of Santorini – that is … comparable to Chalki of Rhodes (Rackham and Vernicos, … and from two sites in the Akrotiri on the north coast of Crete (Moody et al., forthcoming). www.therafoundation.org/articles/environmentflorafauna/.

[6] Iliadis (1950), a first hand source, inform us that there was vegetation exploitable for pasture and fuel as well as buildings on the sattelite islets: a church on Agios Antonios on Atrakousa, and a church of Agios Theodoros on the larger islets of Aï Thoros, where existence of a wind mill, of a drystone kyfi and of an inpluvium cistern is also mentioned (Iliadis, pp. 145-48. 371).

[7] Dry stone walls, terraces with kyfes, enclosures and underground storage areas compose a well structured built landscape similar to what is found in other parts of the Mediterranean (see illustrations).

[8] Eliadis (1950) names seven minoria: τα Κάντια, η Αρέτα, οι Δυο Γυαλοί, ο Λευκός, το Κεφάλι, τα Πηγάδια and η Τραχεια. It is further indicated that they were managed by the Commune which allocated the pastures to specific shepherds (p. 252).

[9] Till the end of the 1940’s the traditional agricultural system involved a form of three-field system in which arable land was divided into three areas. Each of the three field areas was rested in turn for a year. Fallow land was turned into pasture. Animals were allowed to graze after in the area.

[10] Nicander, Theriaca 150, Archiv fur Papyrusforschung, 7, 10. On Mainland Greece (Phokis, Euboea) the word armakies for stone piles is still in use.

[11] Rackham O. (1983), Boetia, p. 323.

[12] Presumably they were tapped for turpentine, which originally came from this tree (not from pines) and is named after it. Small quantities of terebinth turpentine were still produced in the late nineteenth century in Chios and Cyprus (2. Wiesner 1900).

[13] Three or four olive trees are planted inside roofless houses in Chorio to preserve ownership rights. According to informants and documentary evidence olives were cultivated in parts of the adjacent isle of Alimnia.

[14] We have seen goats browsing Opuntia they have reached climbing on a low wall.

[15] In May 1999 we have seen similar vivid brown-red coloured Euphorbias on the islet of Gyali, and there were several leafless plants on the islet of Pergusa on September 3, 2000 (Vernicos).

[16] According to Iliadis, Chalki produced annualy a sizeable quantity of 3 sorts of almonds (p. 248) namely the φουντουκάτα, αφράτα and πετραμύγδαλα varieties.

[17] Rackham 1982: «Land-use and the native vegetation of Greece».

[18] Carob trees are mentioned in written contracts of 1908-1924 (Chalki Municipality archives).

[19] Davis vol. 5.

[20] A large Pistacia terebinthus (αδραμμιθιά) was a typical feature of Saint John’s Konda church (Iliadis, p. 328).

[21] Iliadis p. 327 mentions the yellow cliff flower “athanatos” used for the decoration of Saint Georges’ at Signi (Σίγνη) church in late spring.

[22] Davis vol. 2.

[23] Rackham 1982: «Land-use and the native vegetation of Greece».

[24] Greuter 1966.

[25] Davis vol. 8.

[26] Aerial photographs we have been able to consult in 1994 shows that Alimnia was, in the past, entirely terraced (Vernicos, see below the image).

[27] Apparently made out of Melian obsidian.

[28] Randolf 1687. Vernicos has taken in 1990 several photographs of the cypresses that are now covering extensive areas on the island of Symi.

[29] Iliadis 1950, pp. 145-48 and 253.

[30] Rabbits have been introduced and liberated recently. Also a fair number of partridges are hunted during the hunting season.

[31] Rackham 1983 Boetia and Rackham, 1991 Karpathos.

[32] Pitchler 1883.

[33] Gerola 1916.

[34] Iliadis 1950.

[35] Susini 1965.

[36] Antoniou 1976.

[37] Renfrew 1972.

[38] This arrowhead on the surface of the Alimnia settlement was seen and discussed by a team composed of Prof. N. Moutsopoulos, Dr. J. Volonakis, Dr. Ch. Papachristodoulou and Prof. N. Vernicos; it was left on the spot.

[39] For this we are partly indebted to Dr. J. Volonakis.

[40] Strabo X.v.15.

[41] Theophrastus, Hist.Plant.,VIII.ii.9.

[42] Gerola 1916.

[43] Randolph 1687.

[44] Spratt 1865.

[45] In March 1991 the population fell to 281 persons, at that date the total area of the municipality was 3,704.3 ha and included Chalki, Alimnia and the adjacent islets. Since that date Imborio has profited from a number of new equipment were built in Imborio; there is a Conference Center and the island can now house a fair number of summer visitors. In the 2001 census the population increased to 313 persons.

[46] Iliadis provides information on the islands vines and past wine production (pp. 242-243) indicating that in the 1940s some vineyards only survived in Zies, Pondamos and Ai Yannis o Alarga. He also enumerates seven places where «linoi» were still visible in his times.

[47] Modified version by N. Vernicos.

[48] Skandalides 1982.

[49] Sykesi (Συκήσι, ο κάος της Συκιάς); Loththi (Λόθθι) according to Liddell-Scott dictionary olonthos, erineos (όλονθος, ερινεός): edible fruit of the wild fig; Santaloperivolos named after a fig variety called Sandalos (Σανταλοπερίβολος).

[50] These are: the Λεμονάτα, Μελιτατα, Φούλλικα and Νισύρικα white figs; the Μεαλόμαυρα, Μαυρα black figs, the wild αγρισόσυκα κοκκινερα and the Περδικάτα figs. During subsequent visits in the island, we only saw relatively small white figs. (Vernicos).

[51] Κριθάρια, Αγκιναριές-Αγκύναρος, Κράμπια, Καλάμους, Αλιμούντα, Τριανταφυλλιές.

[52] Αμπέλα, Αχλαδιά, Χαρουπιά, Ροδιά-Ερογιά.

[53] Ασκινάγια, Αρόυνας, Αλισφακιά, Μαρόνι.

[54] Πευκιός, Πευκωτή, Στροϊλιά.

[55] Skandalidis 1982; 20 and Chalki municipality codices.

[56] It should be noted that there several place-names in the Aegean islands refer to Phoenix, either in the form of Finik-/Finikia or as Vaya/Vayes.

[57] In this respect also see here, in fine, a reference taken from Louis Robert (Vernicos).

[58] Quercus macrolepis is recorded from the island of Nysiros, seat of the Asanti, the feudal under-lords of Chalki, who restored the castle’s fortifications.

[59] Philippides 1985.

[60] Rackham 1983 Boetia and Rackham, 1991 Karpathos.

[61] Paepe 1986.

[62] Gerola 1916.

[63] NV: People also ate snails, some fish and mollusks and the occasional migratory birds (quails etc.).

[64] 3. Rackham 1982.

[65] Κατοικιά, σταυλί.

[66] It should be noted that partridges abound. There is also a sizeable rat population on Chalki.

[67] 1983 Boetia and Rackham, 1991 Karpathos.

[68] Αλιπράντης, Νίκος Χρ. ‘Δριός Πάρου: Από την Προϊστορική στη Σύγχρονη Εποχή’. Έκδοση Συλλόγου Οι Φίλοι του Δριού, 2005.

[69] Υπενθυμίζουμε ότι ο Στράβωνας, 10.4.11 (Loeb V, 136-7) αναφέρει ότι το δεύτερο επίνειο της Γόρτυνας ήταν το Μάταλον, θέση που απείχε 130 στάδια από την πόλη. Το εμπόριο όμως της Γόρτυνας βρίσκονταν στην ακτή της Λιβυκής θάλασσας στη θέση Λεβήνα.

[70] Βοκοτόπουλος Λεωνίδας, Το κτηριακό συγκρότημα του φυλακίου της θάλασσας στον όρμο Καρούμες και η περιοχή του. Ο χαρακτήρας της κατοίκησης στην ύπαιθρο της Ανατολικής Κρήτης κατά τη νεοανακτορική εποχή, Θεσσαλονίκη, 2007 (Διατριβή).

[71] Χάλκη και Αλιμνιά, παρατηρούμε πως στην επίσημη μετάφραση του Οθωμανικού ναυτικού πιλότου χρησιμοποιούνται οι παλιές ονομασίες των νήσων, ενώ στο κυρίως κείμενο των δίγλωσσων Ημερολογίων τα νησιά αναφέρονται με τα σημερινά τους ελληνικά ονόματα (Τήλος, Χάλκη, κτλ.)

References

Antoniou, E.B.: Αντωνίου Ε. Β. «Επισκόπηση της Χάλκης της Δωδεκανήσου κατά την αρχαιότητα». Δωδεκανησιακά Χρονικά, 5, σελ. 97-135.(«Episkopisi tis Chalkis tis Dodekanisou kata tin archaiotita». Dodekanisiaka Chronika, 5, 97-135.)

Bintliff, J. (1977). «Natural environment and human settlement in Greece, based on original fieldwork». British Archaeological Rep. Suppl. Ser. 28.

Chalki Municipality codices B 237/1882, B 297/1885, A 57/1884 (Vernicos N.; eds.)

Davis, P.H. (1975) Flora of Turkey and the East Aegean Islands, vol. 5. Edinburgh University Press.

Davis, P.H.: Idem. vol. 8 (1984)

Gerola, G. (1916). «I monumenti medioevali delle tredici Sporadi», parte seconda. Annuario Regia Scuola Archeologica di Atene e delle Missioni Italiani in Oriente, 2, 6-12.

Greuter, W. (1967). Beitrage zur Flora der Sudagais 8. Bauhinia, 3, 243-250.

Iliadis K.: Ηλιάδης Κων/νος Κ. (1950). Η Χάλκη της Δωδεκανήσου (Ιστορία-Λαογραφία- ήθη και έθιμα). Αθήνα, τόμος Α΄ (I Chalki tis Dodekanisou. Athens.) εικόνες, χάρτης.

Paepe, R. (1986). «Landscape changes in Greece as a result of changing climate during the Quarternary». Fantechi, R. and Margaris, N.S. (eds). Desertification in Europe. Dordrecht, Reidel, 49-58.

Philippides, D. (1985). Karpathos. Athens, Melissa.

Pichler, T. (1883). in Stefani, C. de, Forsyth Major, C.J. and Barbey, W. Karpathos. Lausanne 1885.

Rackham, Oliver. (1982). «Land-use and the native vegetation of Greece». Bell, M. and Limbrey, S. (eds.), Archeological Aspects of Woodland Ecology, British Arch. Rep. International Series 146, 177-197.

Rackham, Oliver (1983). «Observations on the historical ecology of Boetia». Annual British School at Athens, 38, 291-351, Plates 34-38.

Rackham, Oliver and Moody, Jennifer (1987). The Making of the Cretan Landscape. Manchester University Press, (ISBN-10: 071903647X)

Rackham, Oliver (198…). Observations on the Historical Ecology of Laconia.

Rackham, O. (Febr. 1991) «Karpathos». Grove A.T., Moody, Jennifer and Rackham Oliver. Crete and the South Aegean Islands (effects of changing climate on the environment ). Geography Department, Downing Place, University of Cambridge, E.C. Contract EV4C-0073-UK.

Rackham, O. & J.A. Moody. (1992). Terraces. Στο B. Wells (επιµ.), Agriculture in Ancient Greece, 123-130. Stockolm. Rackham.

Randolph B. (1687). The Present State of the Islands in the Archipelago…Candia and Rhodes. Oxford.

Renfrew, C. (1972). The Emergence of Civilisation. London, Methuen.

Skandalides, M.E.: Σκανδαλίδης, Μ. Ε. (1982). Το τοπωνυμικό της Χάλκης Δωδεκανήσου. Αθήνα. (To toponimiko tis Chalkis Dodekanisou. Athens.)

Spratt, T.A.B. (1865). Travels and Researches in Crete. London, Van Voorst.

Strabo. Στράβων. X.v.15.

Susini, G, (1965). «Supplemento epigrafico di Caso, Scarpanto, Saro, Calchi, Alimnia e Tilo». Annuario Scuola Archeologica di Atene, 41-42, 255-246.

Theophrastus. Θεόφραστος. Hist. Plant. VIII.ii.9.

Vernicos Nicolas (1986). Chalki in the Dodecanese. Working Paper for the Seminar On Upgrading Chalki’s Natural: Social and Economic Environment, Chalki, 9th-16th May 1986, Athens, May 1986, 54 p.

Wiesner, J. (1900-3). Die Rohstoffe des Pflanzenreichs, 2. Ausg. Leipzig.

© 2009, Oliver Rackham – Nicolas Vernicos

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Writers are the copyright holders of their work and have right to publish it elsewhere with any free or non free license they wish.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Writers are the copyright holders of their work and have right to publish it elsewhere with any free or non free license they wish.